From the preface of the book:

Houses have always existed as part of human habitation, reflecting their culture and beliefs. No building better illustrates architecture as a respond to the physical needs and spiritual desires of man than a house. Therefore, houses are unique entities in the context of cultural studies, or in terms of space creation and architecture of any ethnic group. They are also significant components of the history of architectural development.

Despite this significance, information on house architecture is truly limited due to reasons beyond this discussion. This negligence is also present in architecture books. Fortunately though, five volumes of the Ganjnameh series introduce houses, three of which have been published—vol. 1: Houses of Kashan, vol. 4: Houses of Esfahan, and vol. 14: Houses of Yazd. Volumes 15 and 16 also introduce traditional houses of 24 other cities, totaling 71 houses.

The number of introduced houses in each city is different; 13 houses in one, and 4-8 houses in five other cities. This is either because of the accessibility of houses and their documentations, or because of the degree of integrity of remaining houses in each city. Architectural value and authenticity of houses were among other selection criteria.

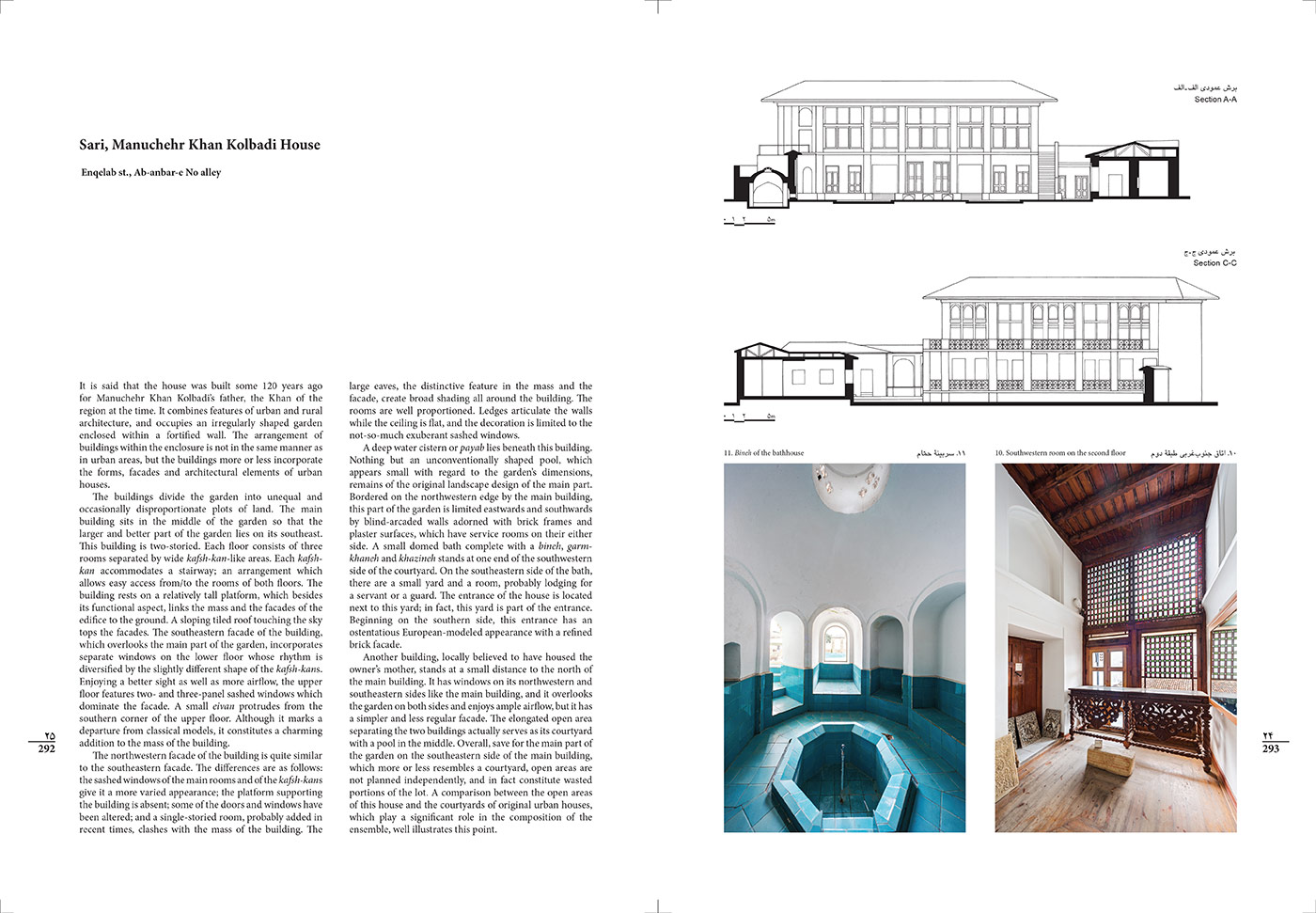

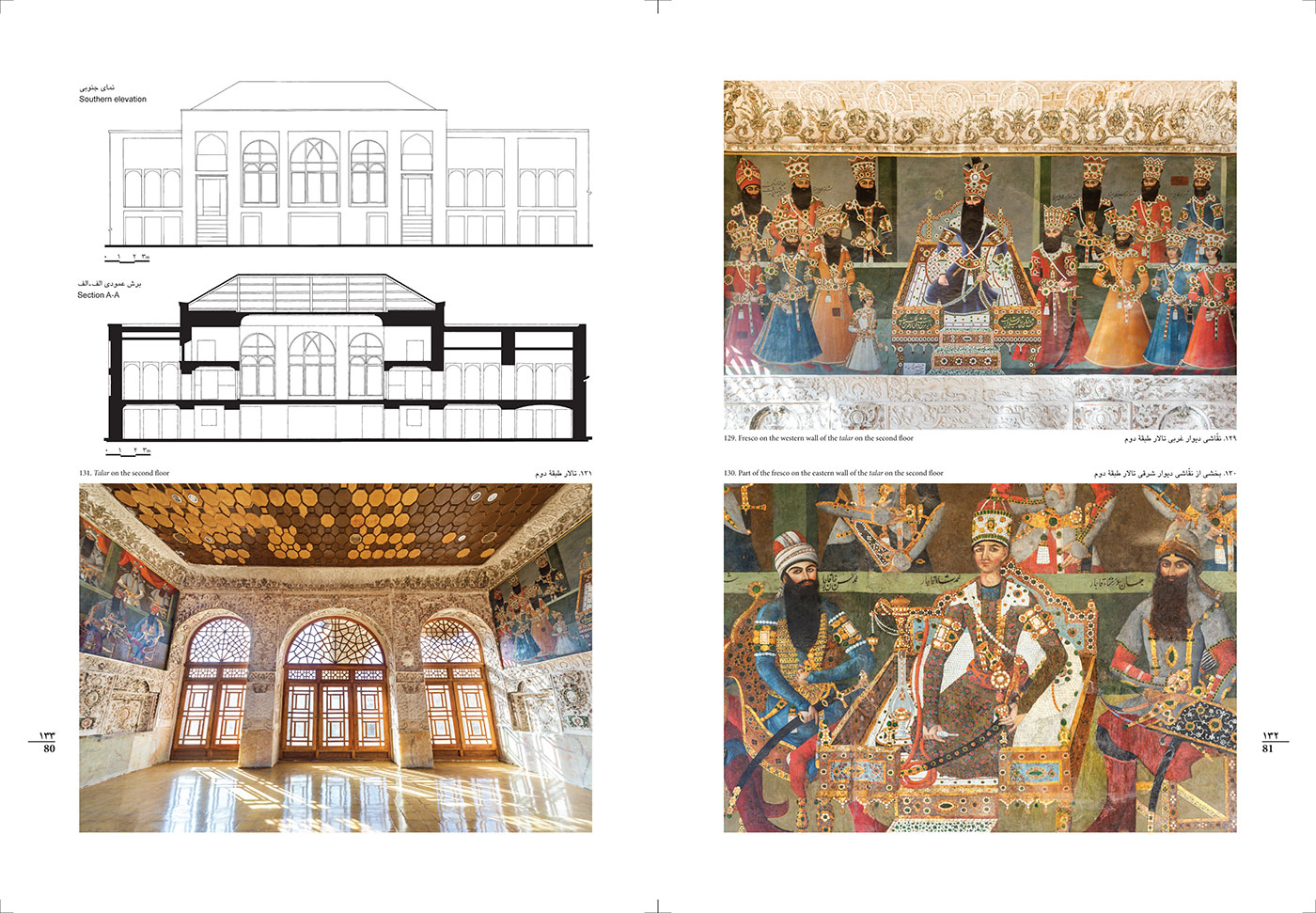

Houses often lack precise construction dates. However, houses presented in these two volumes can be estimated to be built in the thirteenth to the mid-fourteenth century AH, which is contemporary with the Qajar rule in Iran. A few may belong to the early Pahlavi period as well. Therefore, this collection of houses is, in fact, reflective of house architecture during the Qajar era, and highlights the tastes and trends in space creation and house design during the transformation period of Iranian architecture.

Except for few examples dating to the Safavid and Zand era, most traditional houses remaining in Iran are from the Qajar period. Therefore, architecturally, they comprise the most significant evidences by which one could learn about the spaces of normal life in previous times. Nevertheless, it has to be taken into account that this is a prominent architectural period in terms of innovative and ingenious space creation whose most evident examples are in houses.

The pleasant memories of traditional houses in the minds of present Iranians comes from the experience of houses of this period; the experience of amiable, delicate, and fine spaces which induce peace in our body and soul, and let imagination fly. This modest architecture is composed of simple materials, yet in an ordered organization and accounted measures and proportions and a skillful composition. The fine spaces are created by means of precise and proper use of all the qualities of materials, light and shade, water, sky, and plants. In other words, we are dealing with the art of architecture, both in its general and specific senses.

The houses introduced in volumes 15 and 16 of the Ganjnameh series are from different cities across the geographical extent of present Iran. They are all at once representative of the architectural variety of the remaining houses in different regions, as their similarities and differences are illustrated. Nevertheless, they cannot be used to draw an all-inclusive conclusion, since houses of some other cities are missing from the collection. Moreover, the number of houses from some particular cities is not as sufficient to understand and assess local residential architecture. However, our aim has been to illustrate the general composition of residential architecture and space creation of the last centuries by the collection of houses introduced in these two volumes as well as other houses introduced in previous volumes.

Kambiz Haji-Qassemi

winter 2015

The majority of the photographers of Ganjnameh, Volumes 15 and 16 from 1995 until 2001 were Keivan Jourabchi, Navid Mardoukhi Rowhani and Behnam Qelich-Khani. The rest of the photos of these volumes were shot by Hossein Farahani in 2015. Both of these volumes were published in 2016.

Some pages of volume Fifteen; Houses (part 1 ):

Some pages of volume sixteen; Houses (part 2 ):